A staggering 4 in every 10 non-diabetic American adults under the age of 44 experience insulin resistance, a condition where your cells don’t properly respond to insulin [5]. But what causes insulin resistance, and how can you tell if you’re developing it? Even more importantly, can you reverse it?

What is insulin resistance?

Insulin resistance is a metabolic condition brought about by factors such as a diet high in processed, high-carbohydrate foods; a sedentary lifestyle; excess body fat; genetics; and some hormonal syndromes like polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) [1].

If left unchecked, it can progress to pre-diabetes, in which blood sugar levels are higher than normal, and then on to Type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and other cardiovascular problems [2-4].

To fully understand insulin resistance, we need to say a bit about glucose, a simple sugar found naturally in a variety of foods, including starchy vegetables and grains such as corn, rice, potatoes, and wheat, as well as honey and fruits.

Glucose and insulin: partners in energy management

Your body breaks down all the carbohydrates you consume into glucose, its preferred energy source.

We’ve evolved to depend on glucose because it’s the most abundant monosaccharide (simple sugar) in nature, and the easiest to be converted into energy by mitochondria, the engines of our cells [6].

In other words, glucose was essential to our survival in the pre-agricultural conditions in which our ancestors lived, where sugary and fatty foods (read: high-calorie and energy-rich) were scarce and hunter-gatherers sometimes roamed up to 500 miles to search for food [7, 8].

Before supermarkets existed, our ancestors might have gone most of the day with little food before encountering a trove of honey, a cluster of bananas, or another sugary food. To keep a steady supply of energy, the body needed to store additional calories for later — and evolved to deal with this situation by utilizing a hormone called insulin [9].

Glucose is your body's preferred energy source. If you think of glucose as "money" for the body, insulin is the "money manager" hormone.

If we think of energy as money, insulin can be considered the “money manager” hormone.

In life, when you get a sudden cash influx, you decide, based on how much cash you have on hand and how much you need for your current expenses, whether to spend it, put it in a checking account, or put it into a long-term savings account.

In the body, insulin performs a very similar role, directing glucose to where it should go based on the body’s current needs.

Let’s say you just ate a ripe banana and a PB&J on white bread. Here's what happens:

- Your blood glucose levels will rise due to your sudden large intake of carbohydrates.

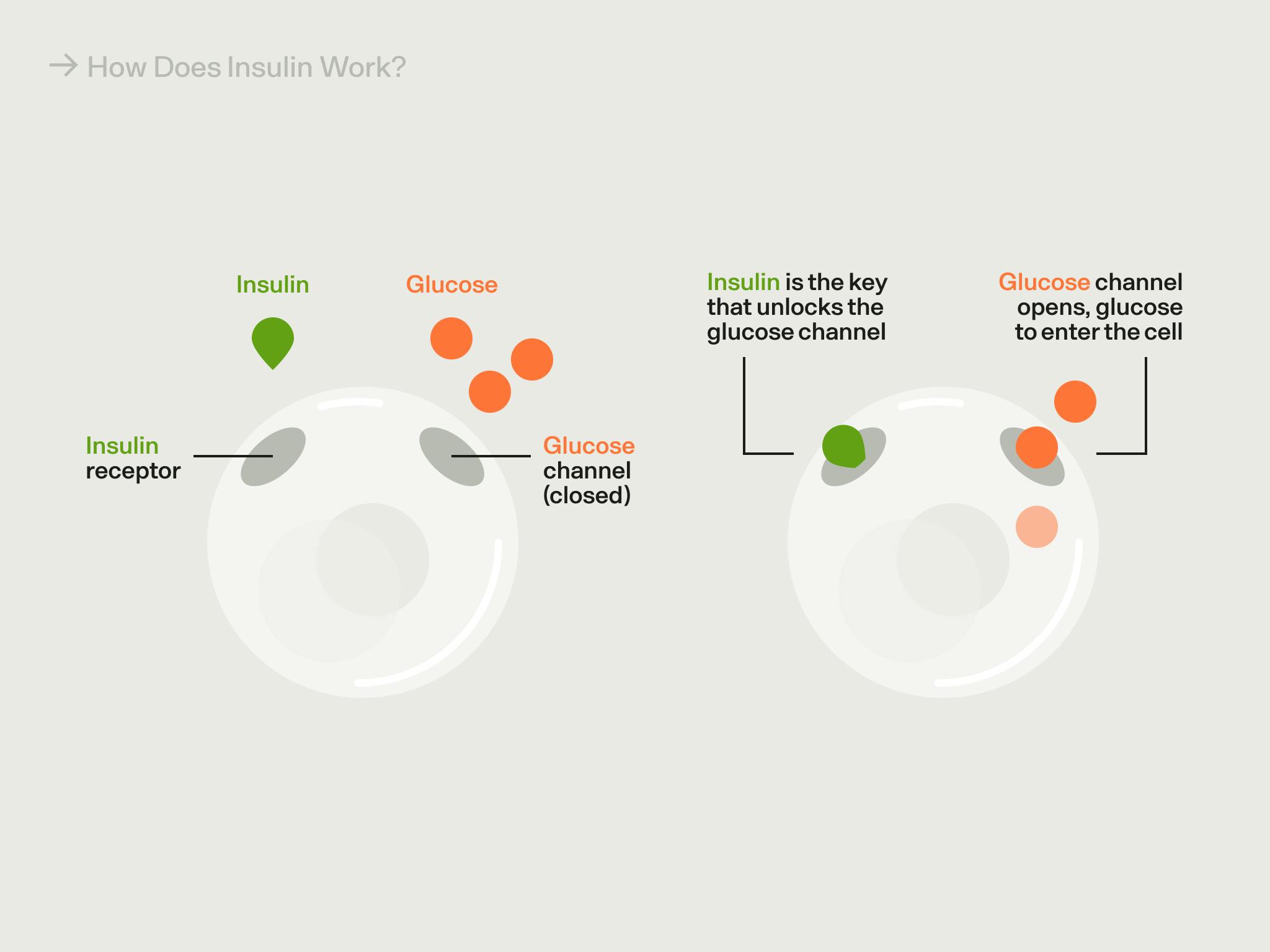

- In response to this biochemical “cash infusion,” the pancreas (an organ near your stomach, liver, and gallbladder) releases insulin, which carries the glucose into cells via specialized transporters [10, 11].

- The first order of business is for insulin to transport glucose into cells that need to use it right away, like active muscle cells.

- But if there’s more glucose than the cells need for current “expenses” (i.e., if there’s more glucose than is necessary to put to use in the cells immediately), the insulin sends the glucose to be built into a short-term storage molecule called glycogen. Glycogen is like a checking account. It stores energy but is easily broken down to withdraw that energy when needed. A small amount of glycogen is stored in the muscles and other cells for their own use, but most is stored in the liver, where it can be broken down into glucose that's released into the blood for use by any cells in the body, including brain cells.

- Once the body’s stores of glycogen fill up, any excess glucose remaining in the bloodstream is converted into fat and stored in adipose (fat) tissue, which you can think of as a savings account or rainy-day fund [12]. While this is natural, storing too much fat — particularly around your waistline and heart — increases your risk of developing metabolic syndrome, diabetes, heart disease, and more.

Why does insulin resistance matter?

The immediate effects of insulin resistance can take a toll on your day-to-day performance, too. Symptoms like poor sleep, fatigue, and trouble concentrating are common with insulin resistance, and can make it difficult to function [21, 22].

One of the primary challenges of insulin resistance is that it can trigger a vicious cycle where you develop cravings for high-carb foods that impair metabolic health and make insulin resistance even worse [23]. As you consume more and more high-carb foods, your glucose levels spike, triggering your pancreas to release extra insulin to bring those levels back to normal. But since your cells aren’t responsive to insulin, you may be stuck in a state of high glucose and high insulin, which leads to weight gain and increased fat storage that’s difficult to manage.

What causes insulin resistance?

When we consistently consume a diet high in glucose (an easy feat in the modern world, where we have 24/7 access to processed snacks and beverages), our insulin-based storage system becomes stressed.

Essentially, the glycogen storage capacity of your muscles and liver maxes out, and excess glucose is converted into fat storage. While some of this fat may be deposited under the skin (subcutaneous fat), your body also deposits fat around your organs that isn’t visible (visceral fat). Researchers have found that one contributor to insulin resistance is this kind of hidden fat, which is biologically active and can release inflammatory hormones and compounds that promote insulin resistance [13].

Where fat ends up (subcutaneous or visceral) depends on a number of factors, including your genes, birth weight, hormones, and age — but visceral fat is more responsive to changes in your diet and exercise routine [37]. In other words, eating processed, high-sugar foods and leading a sedentary lifestyle may increase weight and visceral fat, but eating a metabolically healthy diet and exercising regularly can help metabolize visceral fat.

Since visceral fat is located under your belly muscles and blankets your organs (i.e., you can’t pinch it the same way you’d pinch subcutaneous fat), people who do not appear to be overweight can still have unhealthy amounts of visceral fat and experience insulin resistance.

As a result of the inflammatory hormones and compounds that visceral fat releases, your cells can become less and less responsive to insulin in terms of their glucose uptake, requiring the pancreas to release more and more insulin to do the same job. When insulin loses its ability to effectively shuttle glucose to cells and keep blood glucose levels in a healthy range you develop insulin resistance [13].

Does your risk of insulin resistance increase as you age?

Aging comes with a number of physiological changes, some of which are visible (like wrinkles and graying hair) and others that are not. In fact, as you get older, your risk of developing insulin resistance (or reduced insulin sensitivity) increases, independent of whether or not you live a metabolically healthy lifestyle. In other words, you can be doing all the “right” things metabolically and still experience impaired insulin sensitivity.

Other aspects of aging are also associated with insulin resistance. The decline in estrogen levels during menopause, for example, can make your cells less responsive to insulin and lead to higher levels of blood glucose. And both menopause and andropause (an age-related decline in sex hormones in men) can lead to reduced muscle mass, increased belly fat, and other changes in body composition that can affect insulin sensitivity.

New research also suggests strong links between insulin resistance in the brain and the development of Alzheimer’s disease, which is sometimes called “Type 3 diabetes.”

What is the relationship between insulin resistance and PCOS?

Insulin resistance is associated with polycystic ovarian syndrome, or PCOS. PCOS is a hormonal disorder that’s marked by the presence of ovarian cysts that can disrupt menstruation and fertility, though it often comes with complications such as insulin resistance, increased risk of cardiovascular problems, elevated androgens (male sex hormones), and belly fat. Scientists have found that up to 75% of women with PCOS have insulin resistance, and having insulin resistance may in fact contribute to the development of PCOS [33].

What are the signs and symptoms of insulin resistance?

Some people with insulin resistance have telltale signs, such as [14, 15]:

- a darkening of the skin around the armpits or the neck, known as acanthosis nigricans

- small cutaneous (skin-related) growths called skin tags or other cutaneous abnormalities

- an enlarged waistline (“apple shape”)

If the situation has become more severe and you’ve progressed into hyperglycemia (high blood sugar), you may feel tired and thirsty while also needing to urinate frequently, or hungry even though you've already eaten [16].

Insulin resistance may have unusual or surprising warning signs that aren’t as obvious, including:

- Hair loss, due to high levels of glucose in your blood that changes your hair’s growth cycle and triggers inflammation that impedes blood flow to your hair follicles.

- Sugar cravings, due to a vicious cycle where your body’s glucose is dysregulated and you begin to crave sweet things to bring your glucose levels back to normal after crashing.

- Lethargy and fatigue, due to your cells being starved of glucose and unable to properly make use of it.

How do you test for insulin resistance?

The best way to tell if you’ve developed insulin resistance is by getting your blood glucose tested at your doctor’s office. Sometimes your doctor will test for glucose intolerance or pre-diabetes instead.

The three most common tests for this are:

- A fasting plasma glucose test, which measures your glucose levels after 8 hours of not eating or drinking.

- An oral glucose tolerance test, in which you’ll take a fasting plasma glucose test, drink a special solution of glucose, and then get your blood glucose levels measured after 2 hours.

- A hemoglobin A1C test, which provides a snapshot of your average blood glucose for the past 2-3 months.

What treatments are available for insulin resistance?

The best way to treat insulin resistance is by making lifestyle changes related to your diet, exercise, sleep, and stress (see below). But your doctor may decide to prescribe you metformin, a medication that sensitizes your cells to insulin and helps keep your blood glucose levels balanced [36]. Metformin, like Ozempic and other GLP-1 agonists, is commonly used to treat Type 2 diabetes. It isn’t explicitly used to treat insulin resistance, but it can help improve the symptoms.

How do you reverse insulin resistance?

If you are showing signs of insulin resistance, there are straightforward steps you can take to reverse it. The two key parts of reversing insulin resistance are (1) improving insulin sensitivity and (2) stabilizing your blood glucose levels.

At Veri, we believe that you can achieve these two objectives and lead a metabolically healthy lifestyle by paying close attention to the Four Pillars: diet, exercise, sleep, and stress.

1. Eat a metabolically healthy diet

Nutrition has a powerful effect on insulin resistance. What you eat — and when — can help you stabilize your blood sugar levels and keep you off the glucose roller-coaster, which can quickly escalate into impaired insulin sensitivity.

When it comes to building a metabolically healthy plate, eating fiber is key. Fiber is a great way to lower your blood glucose levels and reduce your risk of developing insulin resistance [30].

One study compared insulin sensitivity in people who ate a high-fiber diet with people who ate a high-protein diet [31]. Both of these groups lost weight in similar amounts (both diets restricted fat to 30% of calories), but they showed a striking difference when it came to insulin: after 6 weeks on the diet, the high-fiber group was 25% more sensitive to insulin than the high-protein group. Similar results have been found in other studies looking at fiber and insulin sensitivity.

Other key aspects of eating a diet that can help you reverse insulin resistance:

- Eating lean proteins and healthy fats for satiety

- Avoiding processed foods and refined sugar

- Experimenting with meal timing and intermittent fasting

- Eating berries, lentils, sardines, and avocados, while avoiding breakfast cereals, french fries, oat milk, and sugar-free sodas (learn why)

2. Exercise regularly

While nutrition can help you balance your glucose levels, exercise is the best way to improve your insulin sensitivity. According to one study, even just one session of moderate exercise can improve insulin sensitivity for up to 48 hours [35]. Another 2017 study found that even less than one hour of resistance training per week (without additional aerobic exercise) reduced the risk of developing metabolic syndrome [26]. Another group of studies found that 2-3 resistance training sessions for at least 8 weeks improved insulin sensitivity by up to 48% [27].

When you exercise, your body breaks down glycogen (your checking account with energy to spend) and frees up glucose to burn during exercise, which in turn clears “storage” space. This can be used to store even more glucose during your next carbohydrate-rich meal, rather than forcing insulin to direct it to your fat cells.

While any and all exercise is good for metabolic health, practicing a mix of resistance training and aerobic exercise can help you improve your body composition and build muscle (which uses more circulating glucose). Five of the best exercises for insulin resistance include:

- Walking

- Squats

- Swimming

- Burpees

- Hatha yoga

As far as the timing of your workout, the best time of day to exercise is the one you’ll stick to consistently. But preliminary research does suggest that mornings workouts are better suited to weight loss and focus/attention, while evening workouts may have a bigger effect on metabolic health.

3. Get better sleep

Sleep is critical to insulin sensitivity, balanced glucose levels, and metabolic health in general. A single night of bad sleep can result in a measurable increase in insulin resistance in healthy people [28]. But getting good sleep involves a few factors, including sleep timing and variability. In other words, not just the time you go to bed and wake up, but the consistency of your sleep routine.

A 2020 systemic review found that later sleep timing and greater sleep variability are associated with increased cardiometabolic risk and other adverse health outcomes [29].

To improve your quality of sleep, it’s important to practice good sleep hygiene. This includes:

- Avoiding food (especially carbs) before bedtime

- Keeping your room cool, between 60-67°F (15-19°C)

- Turning off screens an hour before bedtime

- Getting direct sunlight 0-2 hours after waking

- Using blackout curtains or eye masks

- Eliminating caffeine after lunch

4. Manage stress levels

Chronic stress, where your levels of the hormone cortisol are elevated for a long period of time, can promote insulin resistance and disrupt your metabolic health. This is partly due to the fact that cortisol can naturally hinder insulin secretion, though this doesn’t pose a significant problem in instances of short-term, acute stress [32].

Over time, stress can contribute to long-term insulin resistance by damaging your pancreatic beta cells (which are responsible for producing insulin) and triggering widespread inflammation that makes insulin resistance worse. It can also push you to make bad metabolic health choices, like snacking on processed foods/sugar and exercising less, which keeps you stuck in a cycle of metabolic chaos.

In addition to reducing stress through exercise (even just two days per week of aerobic exercise can help reduce anxiety), studies show that mindfulness practices like meditation can help to reduce your physiological stress response [34]. You can learn other stress management techniques here.

5. Stick to a healthy weight

Insulin resistance can lead to weight gain, which can further promote insulin resistance — causing a vicious cycle that can be hard to break.

One study on adult women between the ages of 24 and 40 found that those who had maintained lost weight demonstrated enhanced insulin sensitivity compared to BMI-matched controls with no weight loss history [24].

On the other hand, women who had previously lost weight but regained it afterward demonstrated impaired insulin sensitivity. Researchers studying overweight and obese women found that maintaining a 15% reduction in body weight for 12 months had improved insulin sensitivity [25].

This doesn’t mean that you can’t effectively lose weight when you have insulin resistance, but that when you focus primarily on reversing insulin resistance (i.e., balancing glucose levels and improving insulin sensitivity), weight loss becomes a natural side effect of the process. This means taking care of your health in other key areas (diet, exercise, stress, and sleep).

How can a CGM help with insulin resistance?

If the two key steps to reversing insulin resistance are improving your insulin sensitivity and balancing your glucose levels, continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) are a powerful tool to help you track your glucose levels. Monitoring your blood sugar levels with a CGM that’s paired with an app like Veri can provide you with a wide array of insights that help inform specific and long-term lifestyle changes, many of which can improve your insulin sensitivity.

Not only can you learn to identify the foods that trigger glucose spikes, but you can understand how your specific responses to exercise timing, sleep patterns, and periods of stress or inactivity are contributing to your glucose levels (and, by proxy, your insulin response).

More importantly, CGMs can empower you with the knowledge you need to combat insulin resistance before it develops into a more serious chronic condition like Type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome. Since the symptoms of metabolic disarray often don’t appear until it’s too late, many people with insulin resistance don’t even know they have it. Using a CGM can help you understand where you fall on the metabolic health spectrum and show you how your glucose levels are fluctuating in real-time (i.e., your glucose variability), which other glucose-tracking methods can’t provide.

Key takeaways

Insulin resistance is one of the leading contributors to our current metabolic health crisis, though addressing it isn’t as simple as eating a healthy diet. In addition to genetic and hormonal conditions, factors such as sleep, exercise, stress, and weight can all enhance or impair your insulin sensitivity — and incorporating the following strategies into your life can help you avoid insulin resistance altogether or reverse it:

- Weight impacts your insulin response, and losing excess weight (and maintaining it) can improve insulin sensitivity.

- Get at least one hour of resistance training per week to reduce your risk of developing metabolic syndrome, and 2-3 resistance training sessions per week for at least 8 weeks to improve insulin sensitivity.

- Improve your sleep timing (when you go to bed and wake up) as well as your sleep variability (how consistently you stick to a sleep schedule).

- Consistently eat fiber with your meals, which minimizes glucose spikes and has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity.

- Manage your stress levels with at least 2 aerobic sessions per week or meditation.

- Monitor your glucose for specific, real-time insights into the role that diet, sleep, exercise, and more impact your metabolic health.

References:

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1204764/

- https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/what-is-diabetes/prediabetes-insulin-resistance

- https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/type2.html

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507839/

- https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/107/1/e25/6362635

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/nursing-and-health-professions/monosaccharide

- https://www.veri.co/learn/the-science-behind-sugar-cravings

- https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/hunter-gatherer-culture

- https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Insulin-human

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279306/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31175156/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4985254/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8831809/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31261473/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8106409/

- https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/managing/manage-blood-sugar.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/type2.html

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31050706/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5409726/

- https://www.veri.co/post/insulin-resistance-and-weight-loss

- https://sleepwhispererpodcast.com/027-insulin-resistance-sleepwith-dr-benjamin-bikman

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20102774/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3554293/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5519190/

- https://www.healio.com/news/endocrinology/20170623/maintained-weight-loss-for-1-year-increases-insulin-sensitivity-in-women

- https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(17)30167-2/fulltext

- https://bmjopensem.bmj.com/content/2/1/e000143

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20371664/

- https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/10.1139/apnm-2020-0032

- https://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/questions-and-answers-dietary-fiber#beneficial_physiological_effects

- https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/94/2/459/4597854?login=false

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4919480/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22192137/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5526744/

- https://www.scielo.br/j/rbme/a/HTX3GCF4FFwkD85trLSvFgm/?lang=en&format=pdf

- https://diabetes.org/healthy-living/medication-treatments/insulin-resistance

- https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/taking-aim-at-belly-fat