Measuring blood sugar is key to understanding your individual metabolic health — but there are many ways to measure blood sugar, all of which vary in method and accuracy.

One popular method used to measure and track blood sugar over time is A1C. While it’s considered the gold standard for monitoring blood glucose, does A1C really give you the whole picture of your blood sugar and metabolic health?

What is the A1C test?

A1C (also called hemoglobin A1C or HbA1C) is a type of hemoglobin — a protein that carries oxygen in your blood [1]. A1C is formed when the glucose in your blood binds to the hemoglobin in your red blood cells. Because of this, measuring A1C can give you a picture of your average blood sugar levels.

A1C is calculated based on the amount of hemoglobin in the blood that had glucose attached to it in the prior 3 months [2]. This means that the more glucose there is in the blood, the more glucose each hemoglobin will be carrying. Test results are expressed as a percentage — a higher A1C equals higher average blood sugar levels.

Since glucose can stay bound to hemoglobin for up to 120 days, the A1C test gives us an approximate measurement of blood sugar levels over the last 3 months [3].

There are over 30 different ways to calculate A1C, all of which are based on four biochemical analysis techniques [4]. Because of this, there can be a lot of variability in the results of the A1C test. For this reason, standardizing the results can be tricky [5].

Ranges for A1C levels – what is considered healthy?

Although it may not apply to everyone, A1C is used as a crucial diagnostic tool for diabetes. High A1C levels indicate long-term, elevated blood sugar levels.

The percentage ranges for A1C levels are [3]:

- Normal: 4-5.7%

- Prediabetes: 5.7-6.4%

- Diabetes: 6.5% or higher

The A1C prediabetes range of 5.7-6.4% reflects an average blood sugar level of 117-137 mg/dl (6.5-7.6mmol/l) and means you are at an increased risk of developing diabetes. An A1C level of 6.5% (140 mg/dl or 7.8 mmol/l average) or higher on two separate tests indicates diabetes.

A dangerous A1C level can vary depending on the individual, but in general, very high levels of A1C, such as those above 10%, can indicate poor blood sugar control and a higher risk of developing serious complications from diabetes, heart disease, nerve damage, and kidney disease.

How often should I get an A1C test and why?

Healthcare providers often use the A1C test as part of regular annual health check-ups and to identify any potential health risks. A1C is typically favored over a fasting glucose test because A1C is more accurate at giving an average of your blood glucose level [6]. Fasting glucose only gives you an indication of your blood glucose levels at the moment [1, 2].

Generally, it is recommended that people with diabetes get an A1C test at least two times a year to monitor their blood sugar control [7].

For people without diabetes, A1C testing may be less frequent and can depend on individual health concerns and risk factors. It is important to follow the recommended testing schedule from a healthcare provider, as regular A1C testing can help to identify potential health problems early and allow for prompt and appropriate medical intervention.

If you are experiencing symptoms of insulin resistance, asking your doctor to test your A1C levels at your next appointment can give you insight into your current metabolic health status.

How to calculate A1C with our calculator

If you use a continuous glucose monitor and know your average glucose, you can use our A1C calculate to find your approximate A1C.

What are the limitations of A1C?

While A1C testing is a useful diagnostic tool for identifying diabetes, and can tell you your average blood sugar levels, it does have limitations.

Second, the A1C test is less accurate in people who do not have diabetes. In these individuals, the amount of glucose attached to hemoglobin may be lower, making it more difficult to accurately measure average blood sugar levels [9].

Research also suggests that A1C levels vary between racial and ethnic groups — in fact, one study of 4,000 participants found that Black, Hispanic, American Indian, and Asian individuals had higher levels of A1C compared to white participants, even after adjusting for factors like age, sex, education, insulin resistance, etc. [10].

The lack of standardized testing for A1C levels due to a large number of available tests is also an issue [11, 9]. This can lead to unreliable results depending on the test and method used.

The A1C test does not provide a clear picture of what is working and what is not in terms of managing blood sugar levels. For example, the test does not differentiate between high blood sugar levels caused by diet, exercise, sleep, stress, or other medical conditions [9]. This can make it difficult for you and your healthcare providers to determine the best course of action for improving blood sugar control.

The A1C is a good benchmark to be used intermittently, but to better understand daily variability, weekly trends, and lifestyle patterns, a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) is a useful tool for getting a comprehensive picture of blood sugar control.

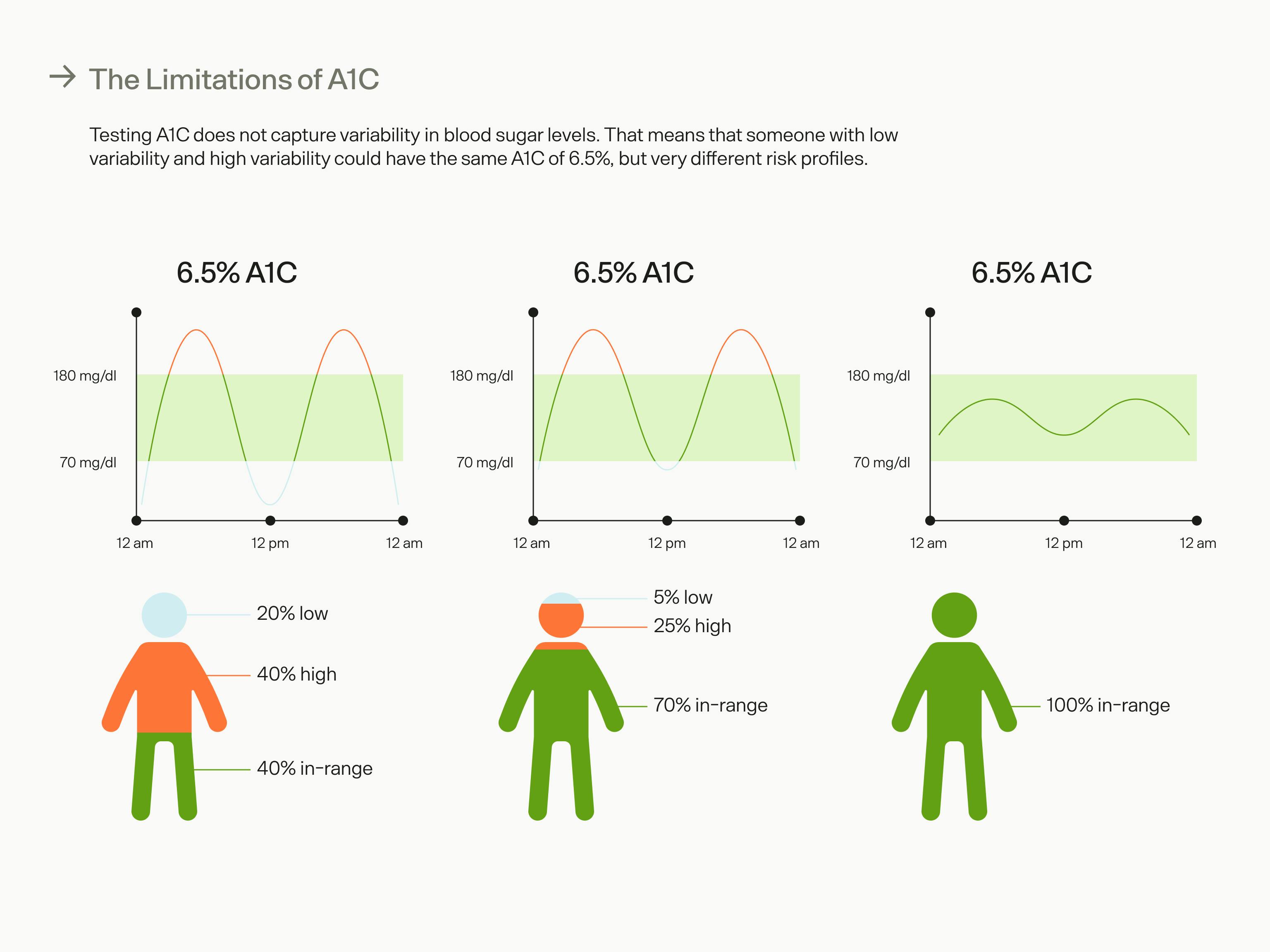

A1C doesn't give you a complete picture of your metabolic health. Three individuals with the same A1C can have different risk profiles based on their glucose levels and variability.

Continuous glucose monitoring vs. A1C

Continuous glucose monitoring provides real-time blood sugar levels by measuring glucose levels in the interstitial fluid (the fluid found between cells that bring nutrients and oxygen from the blood to cells). Compared to the A1C test, CGMs can be useful — especially for non-diabetics — because they provide more detailed information about blood sugar levels and how they are affected by lifestyle habits.

While it is undoubtedly useful for diagnosing diabetes and monitoring populations of people, A1C alone does not give much information on what’s actually going on with an individual’s blood sugar. Changes in blood glucose levels, even throughout a single day, can impact almost every aspect of your life, including fertility (in both men and women) and heart health. Regular monitoring provides a more complete picture of how blood sugar is affecting your metabolic function and health outcomes.

Since metabolic health is a spectrum, the information a CGM provides can be particularly useful for non-diabetics who are looking to increase their healthspan and prevent the development of chronic health conditions, as daily monitoring can alert you of metabolic dysfunction much more quickly than a single A1C test every year. Even the “healthiest” people can learn about how stabilizing your blood sugar can improve your health.

Another advantage of CGM over A1C is that it provides real-time information on how different factors affect glucose levels. This can be useful for non-diabetics looking to change their lifestyle to improve their health. For example, by seeing the immediate impact of a meal on blood sugar levels, you can make more informed decisions about what and how much you eat.

By seeing the impact of exercise, sleep, and stress on blood sugar levels, individuals can make more informed decisions about how they manage these factors to optimize their health. Knowing your body’s unique blood sugar responses to different stimuli can help you decide the best time to exercise, whether you should eat before or after a workout, and how to align your biological clock to optimize sleep and nutrition.

Key takeaways

The A1C test is a useful tool for monitoring blood sugar as it provides a picture of a person's average blood glucose control over a long period of time, but it has some limitations that make it less suitable for non-diabetics.

- A1C can help you detect patterns in your blood sugar levels over long periods of time, which can be helpful for diagnosis and monitoring diseases. The more glucose that’s in your blood, the more A1C will be produced.

- Testing your A1C is not a perfect indicator of your blood sugar control, as there are many factors that can affect the accuracy of the test. It’s important to interpret A1C test results in the context of an individual's overall health. We’re not saying the test is useless or unhelpful, but that it’s an incomplete measurement that doesn’t give you insights into your glucose fluctuations.

- Measuring blood glucose levels regularly is typically considered useful only for people with diabetes. However, knowing more about your blood sugar — how it fluctuates and what makes it change — can help you navigate your health. Continuous glucose monitoring can capture daily variability of blood sugar levels and provide real-time information on how different factors affect glucose levels, offering a more comprehensive picture when combined with A1C.

References:

- https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diagnostic-tests/a1c-test

- https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/managing/managing-blood-sugar/a1c.html

- https://diabetes.org/diabetes/a1c

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0009898115001680

- https://www.ngsp.org/docs/methods.pdf

- https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diagnostic-tests/a1c-test#diagnose

- https://europepmc.org/article/med/23804802

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002962918303732

- https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/34/2/518/39254/A1C-Versus-Glucose-Testing-A-Comparison

- https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/97/4/1067/2833118

- https://jcp.bmj.com/content/57/4/344

- https://www.nature.com/articles/nrendo.2017.3

- https://diabetesjournals.org/spectrum/article/34/2/102/32985/Beyond-A1C-Standardization-of-Continuous-Glucose